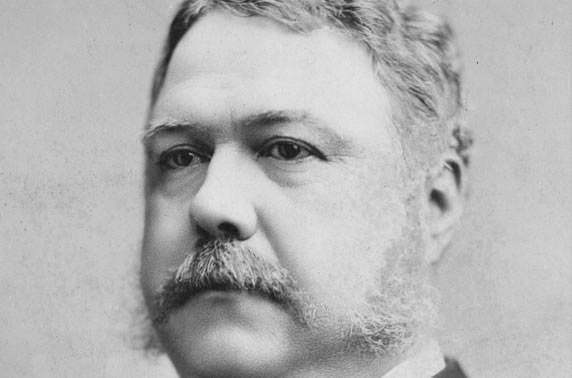

Early Life

Chester A. Arthur was born February 5, 1829, in Fairfield, Vermont, but was raised largely in Schenectady, New York, and other New York villages. He was the fifth of nine children. His father was a converted Baptist minister and staunch abolitionist. In 1845, Arthur enrolled at Union College where he was president of the debate society and doubled as a schoolteacher. In 1853, Arthur moved to New York City where he studied law. He was admitted to the New York State Bar the next year and joined a law firm that was renamed Culver, Parker, and Arthur. Arthur’s law firm would win several high-profile cases involving rights of slaves.

Political Rise

In 1859, Arthur married Ellen Herndon. Together the couple would have three children, two of which survived past childhood. After serving as Quartermaster General for the New York State militia during the Civil War, he returned to a new law practice he established in 1863. Soon, Arthur’s clientele included men associated with New York’s Republican political machine, and Arthur’s political prospects began to blossom. As a result, Arthur began to spend more time in Republican politics than in practicing law. Arthur quickly became a trusted figure in the influential (and corrupt) Republican circles of New York.

Vice President

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Arthur as Collector of the Customs House of the Port of New York, a powerful and lucrative position. In the election of 1880, Republican nominee James A. Garfield chose Arthur as his vice presidential running mate to secure support among New York’s powerful Republican political machine. Garfield and Arthur narrowly won the popular vote by little more than 7,000 votes in an election that recorded the highest qualified voter turnout in history (78.4%). In July of 1881, President James A. Garfield was assassinated, and Chester A. Arthur ascended to the presidency, becoming America’s 21st president.

President

Nicknamed the “Gentleman Boss,” Arthur’s presidency is generally considered successful. He called for civil service reforms and responsible monetary policy. His policies were somewhat surprising given his past connection to corruption and the New York political machine. The crown jewel of the Arthur administration, however, was the 1883 Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. The landmark act, which was passed in response to a scandal in which politically appointed postal workers schemed to steal millions of dollars from the US Government, ensured that government positions would be filled based on a person’s merit rather than politics. In addition, Arthur vetoed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned Chinese people from immigrating to America for twenty years. At the time, many people in America blamed Chinese immigrants for the floundering economy and decrease in overall wages. Although Congress could not veto the bill, a modified bill was ultimately passed that banned Chinese immigration for ten years.

Arthur’s political stances eroded his support in the Republican Party, which refused to nominate him for a second term. Arthur, however, was struggling with kidney disease and was likely too sick to perform duties for another term. Chester A. Arthur died eighteen months after he left office on November 18, 1886.