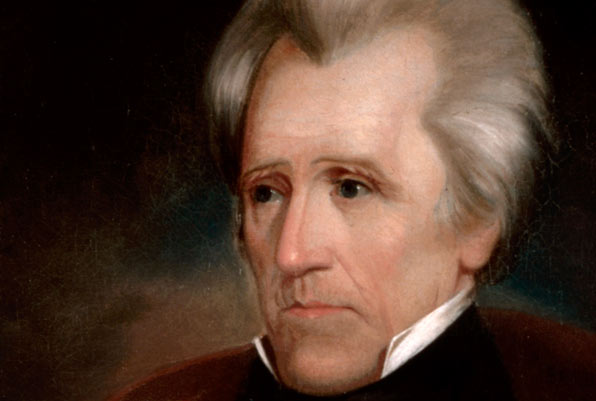

Andrew Jackson |

||||||

|

||||||

Early Life

As a youngster, Jackson experienced no formal education but spent several years reading and studying law. At the age of 20 he was admitted to the bar. In 1788, he was appointed public prosecutor of the western district of North Carolina. He would soon settle in Nashville, Tennessee, and become a successful lawyer. In Tennessee, Jackson met Rachel Donelson Robards who would eventually become his wife. At the time Rachel was married to Captain Lewis Robards, whose bad temper had driven Rachel home to live with her mother who happened to be Jackson’s landlady. They were married in 1791. Jackson and Rachel believed that Captain Robards had received a legal divorce by the Virginia legislature, but the marriage was not officially dissolved until 1793. This stunned the righteous Jackson and the couple was properly remarried in 1794. Jackson’s enemies would claim that he stole another man’s wife and lived with her for three years. These claims did not sit well with Jackson and often invoked his famous temper. Jackson killed Charles Dickinson, a fellow lawyer, in a pistol duel for insulting Rachel. As Jackson continued to prosper in Tennessee, he built his famous mansion, the Hermitage, near Nashville. War of 1812

Controversy

Presidency and Late Life

Jackson believed in the national government and its ability to impose tariffs. South Carolina attempted to nullify the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 that the federal government imposed. South Carolina, like much of the south, was angry that the tariffs would result in higher prices on goods that weren’t manufactured in the south. Jackson, in his typical style, threatened to send in federal troops to enforce compliance with the law. Henry Clay’s Compromise of 1833 prevented final confrontation. In 1832, Andrew Jackson took measures to take away the federal charter of the Second Bank of the United States. Jackson believed the bank was unconstitutional, too powerful, exposed the nation’s finances to foreign interests, favored northeastern states, and was corrupt. Eventually, Jackson succeeded in this endeavor, and the bank’s charter was revoked. Hundreds of state and local banks took over the national bank’s lending functions. Andrew Jackson is perhaps best known for his Indian removal programs. In 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized Congress to purchase Indian lands in the east in exchange for unsettled land in the west. Jackson’s actions were particularly popular in the south, as gold had been discovered on Cherokee lands in Georgia. Jackson pressured Cherokee leaders to sign a removal treaty (known as the Treaty of New Echota) that was surely rejected by most Cherokee people. The treaty, which was enforced by Martin Van Buren (the next president), resulted in the removal of the Cherokee Indians from their native lands via the Trail of Tears. The Cherokee were forced to walk hundreds of miles from Georgia to present-day Oklahoma. Thousands died along the way. In all, more than 45,000 Indians were “removed” during Jackson’s administration. Andrew Jackson retired to his mansion in Tennessee after his second term. He died on June 8, 1845, at the Hermitage

|

||||||

Full Presidential Biographies |

|||||

| Click a president to learn more! | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||