Gettysburg Address

The Gettysburg Address is widely considered one of the greatest speeches in American history. President Lincoln gave the address on November 19, 1863, at the dedication to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battlefield, which is thought to be the site of largest battle ever waged on the North American continent, proved a turning point in the war. Whereas virtually every major battle of the war occurred or was to occur on Southern soil, Confederate forces under Robert E. Lee hoped to bring the fighting to Northern soil. In the epic, bloody three-day battle, which started on July 1, 1863, Confederate forces were finally repulsed by Union forces, and were forced to retreat back to the southern side of the Potomac River. The horrible battle resulted in over 46,000 total casualties.

Lincoln’s speech, however great, was not the headliner speech at the event. Harvard professor and former Massachusetts Governor Edward Everett preceded Lincoln and talked for two hours. In fact, the date of the ceremony was postponed in order to allow Everett enough time to compose the speech. The president’s 272-word address lasted only several minutes. Immediate reaction to the speech was mixed, with some publications praising it and others denouncing it. Generally, those who supported Lincoln praised the speech and those that opposed him bashed it.

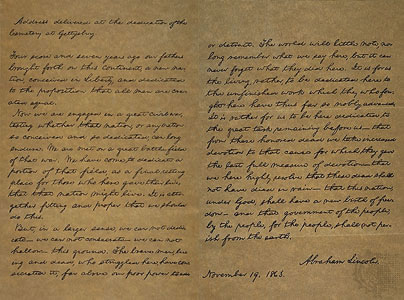

Today there are five known original copies of the Gettysburg Address. Lincoln made a copy for his two assistants, John Hay and John Nicolay. He also made one for Edward Everett, George Bancroft and Colonel Alexander Bliss. The Bliss copy is the copy that is most often re-printed because it was signed by Lincoln himself. It will forever hang in the White House, a condition required by its former owner, Oscar Cintas, after willing it to the American people.

Actual Text from the Gettysburg Address

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Translation: 87 years ago, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and the rest of the Founding Fathers founded a new nation. The nation was founded on the ideals that all people are created equal. Now we are experiencing a Civil War, which is testing whether a nation that holds those ideals as important can survive. We have a gathered at one of the war’s most important battlefields. We will dedicate a portion of that field as a cemetery for those that died here for those ideals. It is important that we as a nation honor them. In a larger sense, we as civilians cannot dedicate this ground. It has already been dedicated by those that died here, and we, as civilians, can only speak of their sacrifices. The world will forget about those words, but not of the sacrifices made by the soldiers who fought here. Our jobs, as civilians still living in this country, is to ensure their work here, which has brought this war closer to an end, continues until the country is brought back together. That we, as civilians, should be inspired by the deaths of soldiers for this cause, to renew our dedication to that cause, and to make sure the deaths of those soldiers did not occur for a lost cause. Finally, that our nation, under God, will re-define its idea of freedom as freedom for all people and that government reflective of the will of its people will not prove impossible.

|