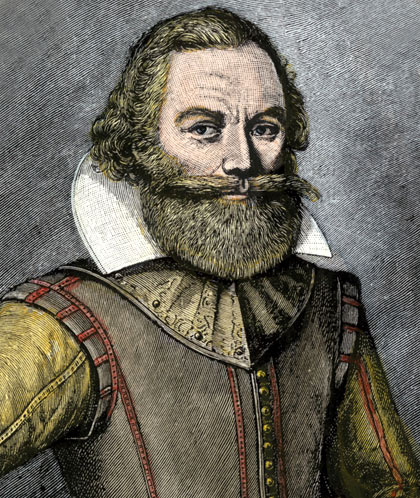

Born in January of 1580, John Smith is most widely known as a leader of the Virginia Colony and played a major role in establishing the first permanent English settlement, Jamestown. He also led exploration parties along the rivers in Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay, and was the first English explorer to map the Chesapeake Bay area. John Smith’s experiences in England established him as an experienced soldier and a fearless explorer. He grew up on a farm at Willoughby near Lincolnshire, but left home to set off for adventures at sea at the age of sixteen after the death of his father. Smith first served as a mercenary in France’s army against the Spaniards, and later engaged in both trade and piracy in the Mediterranean Sea. He fought against the Ottoman Turks in the Long Turkish War, and was promoted to captain fighting for Austria in Hungary. Rumors spread that Smith killed and beheaded three Turkish adversaries in single combat duels, for which he received a knighthood, a horse, and a coat of arms depicting three Turkish heads. In 1602, though, he was wounded in a minor skirmish, captured, and sold as a slave. Even in such dire circumstances, John Smith’s luck held out: his master sent him as a gift to a Greek mistress in Constantinople, and she in turn fell in love with Smith. He later escaped and returned through Europe and Northern Africa to England in 1604. In 1606, Smith joined the Virginia Company of London to colonize Virginia for profit. His expedition set sail in the three small ships named the Discovery, the Susan Constant, and the Godspeed. On this lesser known voyage, John Smith was actually charged with mutiny, and Captain Christopher Newport planned to execute him upon landing; however Smith unsealed orders form the Virginia Company assigning him as one of the leaders of the new colony, which saved Smith from a death sentence at the gallows. Settlers arrived in Jamestown in the spring of 1607; after the long, grueling journey across the Atlantic Ocean, their food supplies dwindled to the point where they were forced to ration their meals: settlers received only 1-2 cups of grain each day. They were soon starving and suffering from malnutrition. A number of men died from drinking brackish water, and by September more than half of the settlers who arrived were dead. His personal practices equipped Smith with strong beliefs that he forced upon the settlers in the New World; he required settlers to farm and work, saving the colony from starvation and failure by declaring “He that will not work, shall not eat.” It was with his strong character, ruthless determination, and unflinching work ethic that allowed him to lead the colonists as they faced challenges amongst themselves, hostile Indians, and the harsh wilderness that was Virginia. Under Smith's leadership, people started working, stopped dying, and planted crops, built forts, and sent products back to England. What Smith was unsuccessful in trading for with the local Powhatans, he took by force and intimidation. In December 1607, Smith was exploring and searching for food along the Chickahominy River when he was captured by the Powhatan Indians; he credited his survival and release to the Powhatan chief’s daughter, Pocahontas, who threw herself across his body when he was to be executed. Many historians believe Smith misinterpreted a Powhatan adoption ceremony as an "execution." Either way, he was returned to Jamestown unharmed. Unfortunately, he had to return to England after an injury from a gunpowder explosion. While he never returned to Virginia, he spent his remaining years writing about his vast experiences, including his time in the New World. He died on June 21, 1631, but his legacy and contributions to the establishment of the New World still continue. |